Overview 🔗

This post walks through the process of building and deploying a static blog (or any static website, for that matter), using Hugo, and AWS services like Amazon S3 and CloudFront, as well as showing how to utilise Terraform to deploy the necessary AWS resources as code. In Part 2, we’ll look at how to implement a CI/CD pipeline in AWS.

Before we get into things, you can find the full source code for this blog on GitHub.

Defining the Solution 🔗

We’ve established that we’re going to build a blog or some other website, but the key here is that we’re building a static site, i.e. we’re building a site that doesn’t have dynamic content which means that it doesn’t utilise server-side processing to do things like calling REST APIs or interacting with databases - once we’ve written our content, it doesn’t change and it doesn’t need to rely on any external resources. Whilst this is restrictive for some things (Amazon wouldn’t be much use to anyone if it were static, for example), it’s perfect for a blog and it means that without knowing much about good web development, we can very quickly build an attractive site with minimal effort.

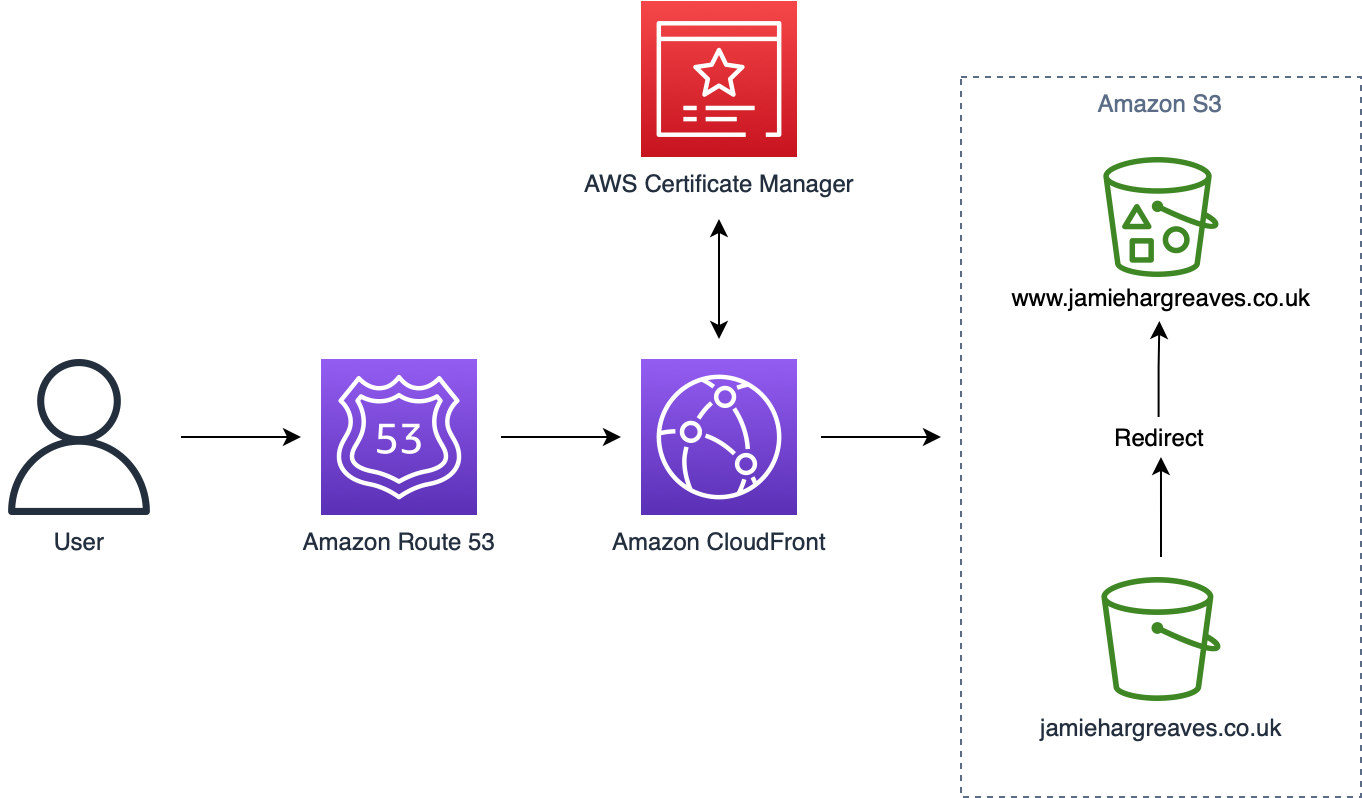

In addition to being much easier to build, the static nature of our site means it’ll also be much easier (and cheaper), to host. For hosting, we’re going to utilise Amazon S3, a cloud object store that supports servicing static web content, and Amazon CloudFront, a Content Delivery Network (CDN). Whilst not strictly necessary, the use of a CDN lets us cache our static content on AWS edge nodes for better end-user performance, rather than making our users go all the way to S3 every time and - if you’re interested, you can read more about how CloudFront handles requests in the documentation. Potentially more importantly, the use of CloudFront is also required if we want to enable connection to our site over HTTPS.

Overall, our solution architecture is fairly straight forward and is going to look like the diagram below, and we’ll discuss each component as we go.

The Blog Itself 🔗

Choosing a Framework 🔗

Okay, so we’ve seen the overall solution, but the first question is how are we going to build the actual blog? Well, there are numerous options and for a while I toyed around with the idea of building a custom site in React.js (and actually made a start on it), however I realised two things in the process:

- Firstly, web-development isn’t my forté; I know enough JavaScript to get by, but when it comes to responsive design and all the other intricacies of building a site that will reliably work across a range of devices, I’m out of my depth.

- Secondly, whilst building your own React application (or using any number of other frameworks like Next.js or AngularJS), is a great way to learn more about web development, it’s also fairly time consuming if you’re new to it and I found it detracted from the purpose of the project which was to start a blog, not to learn web development.

As such, if you’re mostly interested in quickly getting something up and running and actually starting to add content to your blog, I’d recommend the option I ultimately went with: Hugo. Hugo is an open-source web framework specifically designed with static web content in mind and with tons of community support for responsive themes which makes development extremely easy, even if (like me), you’ve little to no web development experience. In addition, blog posts can be written in plain Markdown whilst also supporting some nice extensions called shortcodes if you want to get a bit more creative.

Building the Blog 🔗

The basic structure we’re going to use for the project is as follows (though if you look in the GitHub repo, things will look slightly different since I’ve implement a CI/CD pipeline to along with this; again, see Part 2 for more details on that):

├── infra

| └── policies

└── site

├── app

└── release

I won’t go over the steps to install Hugo and set up a new site since I’d just be re-hashing what’s already covered in the Quick-Start guide, so if you are using Hugo, have a read through the guide and you should be up and running with a new site in a few minutes. Again, there’s no requirement to use Hugo here, you can use any framework that allows you to compile static content. Once you have everything ready, there are a few Hugo CLI commands you can use the to test the site:

# Build static content

hugo

# Build static content, including draft posts

hugo -D

# Run a local development server

hugo server

Getting a Domain 🔗

The first thing you’ll need is a domain for your site and you can buy one from several places - I bought one from IONOS, however you can also purchase a domain directly through AWS using Amazon Route 53.

The Resources 🔗

Let’s establish the resources we’re going to need to deploy.

S3 Buckets 🔗

We already mentioned that we’ll be hosting the site on S3, so we’re going to need to three buckets: one with the www prefix and one without, as well as a bucket to store logs from requests made to our site and a bucket to store configuration files (namely, our Terraform state which we’ll talk more about later).

Hosted Zone 🔗

A hosted zone is a sub-service of Route 53 that we’ll use to determine how requests to our site are routed.

SSL Certificate 🔗

An SSL certificate is a pre-requisite to enforcing HTTPS for all of our web traffic. In essence, when requests are passed to CloudFront, it will pass this SSL certificate to the user’s browser so that the browser knows it can trust our website, after which it will initiate a secure connection over SSL/TLS. HTTPS is obviously important to have from a security perspective, but it’s also worth noting that without it, browsers like Safari or Chrome will show a “Not Secure” flag in the address bar and some anti-virus products may block access to your website unless the user specifically exempts it.

CloudFront Distribution 🔗

The CloudFront Distribution is the resource we’ll use in order to cache our static content, as well as to enforce HTTPS on our site.

IAM Roles 🔗

We’ll need to use several Identity and Access Management (IAM) roles in order to allow various resources to interact with one another and with other AWS services in a secure way but I’ll explain the permissions we’re giving each role as we deploy them. Generally, we’ll try to be as specific as possible when we define the permissions for our IAM roles, following the concept of least privilege.

Resource Naming Conventions 🔗

Throughout the post, I’m going to adopt a fairly standard approach to resource naming which will be as follows:

<resource_abbreviation>-<organisation>-<project>-<description>

This should become fairly self-explanatory once we start to define some resources.

Pre-Requisite Resources 🔗

Before we actually start writing any code, we need to deploy two resources; firstly, a Hosted Zone and secondly, an S3 bucket to hold configuration files.

Let’s start with the Hosted Zone; this needs to be done upfront because my domain is registered outside of AWS, which means once my Hosted Zone is set up, I need to configure the Name Servers for my domain through the IONOS portal. If your domain is registered through Route 53, then a Hosted Zone will already have been created and configured for you as part of the registration process, and you can skip this step entirely. We’ll provision a Hosted Zone using the AWS CLI (see the Getting Started guide if you don’t have this set up), and we’ll use our base domain for the Hosted Zone name (the caller reference just needs to be a unique string, hence why I’m using the current date-time):

aws route53 create-hosted-zone \

--name jamiehargreaves.co.uk \

--caller-reference $(echo date)

Now that it’s set up, we need the Name Server addresses which can then be used to update my IONOS Name Server settings. To do this we need to get the ID of the Hosted Zone we just created (you don’t need to use JQ here but I like to use it since it formats JSON responses nicely):

aws route53 list-hosted-zones | jq

This will return a JSON object whose HostedZones key will contain an array of Hosted Zones; it’ll look something like this:

{

"HostedZones": [

{

"Id": "/hostedzone/Z0827073DSZEQ2F7K5PK",

"Name": "jamiehargreaves.co.uk.",

"CallerReference": "terraform-20211230113612691900000001",

"Config": {

"Comment": "Managed by Terraform",

"PrivateZone": false

},

"ResourceRecordSetCount": 6

}

]

}

We can pull out the Hosted Zone ID in order to take a look at its associated Name Servers:

aws route53 get-hosted-zone \

--id /hostedzone/Z0827073DSZEQ2F7K5PK | \

jq '.DelegationSet.NameServers'

This returns an array of Name Server addresses:

[

"ns-1864.awsdns-41.co.uk",

"ns-9.awsdns-01.com",

"ns-556.awsdns-05.net",

"ns-1344.awsdns-40.org"

]

The configuration of these will depend on where your domain is registered, so you’ll need to look into how to do this for whatever provider you’ve used.

Next, we’ll deploy the S3 bucket (again using the CLI); since we’re using it for configuration data - specifically, to store our Terraform state - I’m going to make the bucket versioned so we can always recover previous versions if needs be:

# Create bucket

aws s3api create-bucket \

--bucket s3-jamie-general-config \

--create-bucket-configuration '{"LocationConstraint": "eu-west-1"}'

# Enable versioning

aws s3api put-bucket-versioning \

--bucket s3-jamie-general-config \

--versioning-configuration '{"Status": "Enabled"}'

Infrastructure-as-Code 🔗

As I mentioned at the start of the post, we’re going to deploy all the resources into AWS using an infrastructure-as-code (IaC) approach rather than manually going into the Management Console and deploying the resources. This isn’t strictly necessary for a project of this size, but I find it’s much cleaner to have all of my resources version controlled as code and much safer if I need to make changes as I’ll be able to see the impact of those changes on my resources before I actually deploy them. I also I think it’s a good habit to get into and, if you’re new to IaC, then a smaller project like this is a great place to practice.

I’ve chosen Terraform to deploy the resources (have a look here if you’re not familiar), but there’s no reason you couldn’t use AWS CloudFormation for this. In general though, I think CloudFormation is overly verbose and often poorly documented (though that’s just my personal opinion). In addition, there are also limitations around deploying resources into different regions within CloudFormation stacks (which can be achieved using StackSets), in situations where we then need to be able to reference the attributes (e.g. the resource ARN), of the resource within that same stack - Terraform doesn’t have this limitation.

Now that’s out of the way, we can start defining the rest of our resources. I’ll do this within a single main.tf file within the infra folder. We’ll start by defining the main AWS provider and a couple of input variables whose values we’ll provide when we deploy the resources. We’ll also enforce that the project reference only use lowercase characters (I think this looks nicer in resource names).

| ❗ Important |

|---|

A really crucial thing to note in this first code block is the use of the backend block within the top level terraform definition. Terraform stores the state of your deployed resources in a configuration file which, by default, is stored locally. The problem here is that if anything happens to your state file (e.g. you accidentally delete it), you can end up with orphaned resources that are no longer registered as remote resources with Terraform. Whilst you could version control this file, this risks compromising sensitive data that Terraform may store in plain text in the state file. For this reason, you should always store your state remotely, in this case in a versioned S3 bucket, and this is the purpose of the backend block. |

# Main configuration

terraform {

required_providers {

aws = {

source = "hashicorp/aws"

version = "~> 3.0"

}

}

backend "s3" {

bucket = "s3-jamie-general-config"

key = "blog/terraform.state"

region = "eu-west-1"

encrypt = true

}

}

# Input variables

variable "project" {

type = string

description = "An abbreviation for the project the resources relate to."

validation {

condition = can(regex("[a-z]*", var.project))

error_message = "Project abbreviation must be lower case letters only."

}

}

variable "created_by" {

type = string

description = "The name of the user who created the resource."

}

I alluded earlier to the need to be able to deploy resources into different regions and this is beacuse CloudFront distributions require all SSL certificates to be provisioned in us-east-1, therefore I’m going to define two providers: one in my primary region of eu-west-1 (i.e. Ireland), and another in us-east-1 (N. Virginia), which I’ll use when I’m deploying the SSL certificate and which I’ll alias as useast. In both, I’m using the default_tags argument which lets us define a set of default tags that are applied to any resources using that provider which support tags:

# Providers

provider "aws" {

region = "eu-west-1"

default_tags {

tags = {

Project = var.project,

CreatedBy = var.created_by

}

}

}

provider "aws" {

region = "us-east-1"

alias = "useast"

default_tags {

tags = {

Project = var.project,

CreatedBy = var.created_by

}

}

}

We now need to define some data sources; these are essentially references to resources or other information defined outside of Terraform itself that we can use within our main.tf file. The three data sources we’ll use are:

- The

aws_regionwhich allows us to get information about the configured region for the current AWS provider. - The

aws_caller_identitywhich allows us to get information like the current Account ID. - An

aws_route53_zonewhich lets us reference the Hosted Zone we created in the previous steps.

# Data sources

data "aws_region" "current" {}

data "aws_caller_identity" "current" {}

data "aws_route53_zone" "hosted_zone" {

zone_id = "Z0827073DSZEQ2F7K5PK"

private_zone = false

}

Next we need to define our S3 buckets. The primary bucket that will be used to store our web content needs to be publicly accessible, whilst the rest of our buckets should be private. In addition, the diagram I showed earlier had an arrow indicating that the jamiehargreaves.co.uk bucket would redirect to the www.jamiehargreaves.co.uk bucket and that’s exactly the case. When a request is sent to the base domain, the only purpose of its bucket will be to forward on those requests to the prefixed domain bucket, which will actually contain the web content (though this could be the other way around and, arguably, should be but it doesn’t make any practical difference). It’s also worth noting that the bucket names for the website itself aren’t optional, you must name your bucket the same name as the domain.

# S3 buckets

resource "aws_s3_bucket" "primary_bucket" {

bucket = "www.jamiehargreaves.co.uk"

policy = file("policies/s3_public_get_object.json")

website {

index_document = "index.html"

error_document = "404.html"

}

}

resource "aws_s3_bucket" "redirect_bucket" {

bucket = replace(aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.bucket, "www.", "")

website {

redirect_all_requests_to = "https://${aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.bucket}"

}

}

resource "aws_s3_bucket" "logs_bucket" {

bucket = "s3-jamie-general-logs"

acl = "log-delivery-write"

}

Here, we’ve assigned our primary_bucket an IAM policy stored in an infra/policies sub-folder which allows anonymous public read access to all bucket objects (you can read more about policy definitions in the documentation):

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "PublicReadGetObject",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:GetObject",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::www.jamiehargreaves.co.uk/*"

}

]

}

We covered the importance of using an SSL certificate in order to enforce HTTPS, so we’ll deploy that next. It’s worth noting that the subject_alternative_name argument here only contains a reference to the redirect bucket since the domain name reference is the fully prefixed version. If we reference both of these domains as alternative names, then the duplicate one will be automatically ignored by AWS in the deployment which means Terraform will detect drift between the resource definition and the actual resource any time we run an apply command, even though nothing has actually changed. In addition, note that I’m using the aliased useast provider here, since certificates needs to be provisioned in us-east-1 in order to work with CloudFront.

# SSL certificate

resource "aws_acm_certificate" "cert" {

provider = aws.useast

domain_name = aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.bucket

validation_method = "DNS"

subject_alternative_names = [aws_s3_bucket.redirect_bucket.bucket]

}

Now that we have an SSL certificate set up, we need to go through the DNS validation process. You can read more in the documentation about how DNS validation works, but the TLDR version is that this process is how AWS establishes that you own your domain.

# Route 53

resource "aws_route53_record" "cnames" {

for_each = {

for dvo in aws_acm_certificate.cert.domain_validation_options : dvo.domain_name => {

name = dvo.resource_record_name

record = dvo.resource_record_value

type = dvo.resource_record_type

}

}

name = each.value.name

records = [each.value.record]

ttl = 60

type = each.value.type

zone_id = data.aws_route53_zone.hosted_zone.zone_id

}

# Certificate validation

resource "aws_acm_certificate_validation" "cert_validation" {

provider = aws.useast

certificate_arn = aws_acm_certificate.cert.arn

validation_record_fqdns = [for record in aws_route53_record.cnames : record.fqdn]

}

If the Terraform looping consruct above looks unfamilar to you, have a look at the documentation to see some examples, but essentially all we’re doing here is accessing the domain_validation_options output from the SSL certificate resource we created previously and adding the Canonical Name (CNAME) records to our Hosted Zone in Route 53 to validate the SSL certificate we created.

Next, we need to add the CloudFront distribution itself. This resource probably requires the most configuration out of all of our resources, however the main things we’re doing here are:

- Pointing CloudFront to the base S3 bucket which will contain our web content.

- Specifying some caching behaviour and enforcing that all traffic be redirected to HTTPS.

- Telling CloudFront where to store site activity logs.

- Specifying the aliases for the Distribution (i.e. the base domain and prefixed domain).

- Telling CloudFront which SSL certificate to use.

# CloudFront Distribution

resource "aws_cloudfront_distribution" "distribution" {

origin {

origin_id = "Primary"

domain_name = aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.website_endpoint

custom_origin_config {

http_port = 80

https_port = 443

origin_protocol_policy = "http-only"

origin_ssl_protocols = ["TLSv1.2"]

}

}

default_cache_behavior {

allowed_methods = ["GET", "HEAD"]

cached_methods = ["GET", "HEAD"]

target_origin_id = "Primary"

viewer_protocol_policy = "redirect-to-https"

forwarded_values {

query_string = false

cookies {

forward = "none"

}

}

}

logging_config {

bucket = aws_s3_bucket.logs_bucket.bucket_domain_name

include_cookies = false

prefix = "blog/"

}

enabled = true

is_ipv6_enabled = true

http_version = "http2"

price_class = "PriceClass_All"

aliases = [

aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.bucket,

aws_s3_bucket.redirect_bucket.bucket

]

restrictions {

geo_restriction {

restriction_type = "none"

}

}

viewer_certificate {

acm_certificate_arn = aws_acm_certificate.cert.arn

minimum_protocol_version = "TLSv1.2_2021"

ssl_support_method = "sni-only"

}

}

The last thing we need to do before we have all the resources we need to have a fully functioning static website is to define two last records in our Hosted Zone in Route 53 which point to our new CloudFront distribution:

# CloudFront alias records

resource "aws_route53_record" "primary_record" {

zone_id = data.aws_route53_zone.hosted_zone.zone_id

name = aws_s3_bucket.primary_bucket.bucket

type = "A"

alias {

name = aws_cloudfront_distribution.distribution.domain_name

zone_id = aws_cloudfront_distribution.distribution.hosted_zone_id

evaluate_target_health = true

}

}

resource "aws_route53_record" "redirect_record" {

zone_id = data.aws_route53_zone.hosted_zone.zone_id

name = ""

type = "A"

alias {

name = aws_cloudfront_distribution.distribution.domain_name

zone_id = aws_cloudfront_distribution.distribution.hosted_zone_id

evaluate_target_health = true

}

}

In theory we can now run terraform init and terraform apply to deploy our resources, then push our Hugo site to S3 and everything should work. If you’re happy to do that and to leave out a deployment pipeline (which is arguably superfluous), then that’s exactly what you can do. From within the infra folder, run terraform init, then run (substituting your project and created_by values as appropriate):

terraform apply \

-var project=blog \

-var created_by=jamie \

-auto-approve

If you want to see the changes Terraform will make before making them, then leave off the -auto-approve flag and you’ll be manually prompted to approve the deployment.

Once all of your resources have been deployed, you can deploy your content to S3. To do so, just add a deployment section to your config.yml:

deployment:

targets:

- name: aws-s3-deploy

URL: s3://www.jamiehargreaves.co.uk?region=eu-west-1

cloudFrontDistributionID: EAWN7FFX2G2YW

Alternatively, if you’re using a TOML config:

[deployment]

[[deployment.targets]]

name = "aws-s3-deploy"

URL = "s3://www.jamiehargreaves.co.uk?region=eu-west-1"

cloudFrontDistributionID = "EAWN7FFX2G2YW"

Note the specific structure the S3 endpoint needs to use, namely s3://<bucket_name>?region=<bucket_region>. Note also that we’ve included the CloudFront distribution ID here which causes Hugo to invalidate any currently cached files - you can read more about the cost implications of CloudFront path invalidation here (TLDR; the first 1,000 are free and after that it’s still very cheap). If you omit the invalidation of CloudFront files, then by default CloudFront will serve up static content for at least 24 hours, meaning you could be serving stale content to your visitors. You can get the CloudFront ID through the CLI:

aws cloudfront list-distributions | jq

This will return a fairly large JSON object showing all Distributions and their associated attributes (including the ID). From here, we can run the deployment from within the site/app sub-folder:

# Build

hugo

# Deploy

hugo deploy

This will push all of your static files to S3, after which your website should be up and running!