Should we bother with Monads in Python? 🔗

In my previous posts in this series I’ve talked at some length about the basics of Functors, Applicatives and Monads in Python, as well as how they fit into functional programming more broadly. To me, the fact that it’s taken this long to give what I would consider to be a sufficiently detailed explanation of how they work is quite telling. Not only that, but I only spoke about two Monads in any detail, Either and IO, but I brushed over the fact that there are all sorts of other Monads designed to tackle different problems and, whilst similar, all these Monads do work differently. As I’ve said before, I don’t think that Monads are particularly complicated in principle, but I do think they’re extremely unfamiliar to most people, especially in the context of Python.

At the the start of this series, the first criterion I said I wanted my code to adhere to was that it easy to read and understand. I’ve argued that the Monadic code we wrote in previous posts fulfils this criterion. After all, remember how nice and readable our code looked when we used things like map and bind and how we could read the code like we were reading plain English? I think this was a bit misleading. Was it really the use of Monads that made our code so easy to reason about? No. We happened to use Monads to compose our functions, but it was function composition and well-named functions that made our code feel so clean. What’s more, what happens if someone needs to add new functionality to our code, say logging? Do they need to start reading all about the Writer Monad and figuring out a way to replicate a Monad transformer or start wrapping Monads in other Monads to handle exceptions when they want to log in the same function?

Monadic Python code is easy to read and understand if you understand how Monads work, but by that logic, isn’t all code easy to read and understand to someone? “Easy to read and understand” should apply to a wider audience than just the person who wrote the code and be deeper than a superficial understanding after a quick once-over. In a professional setting, you’re not the only person who needs to read, understand, maintain, and extend the code you write.

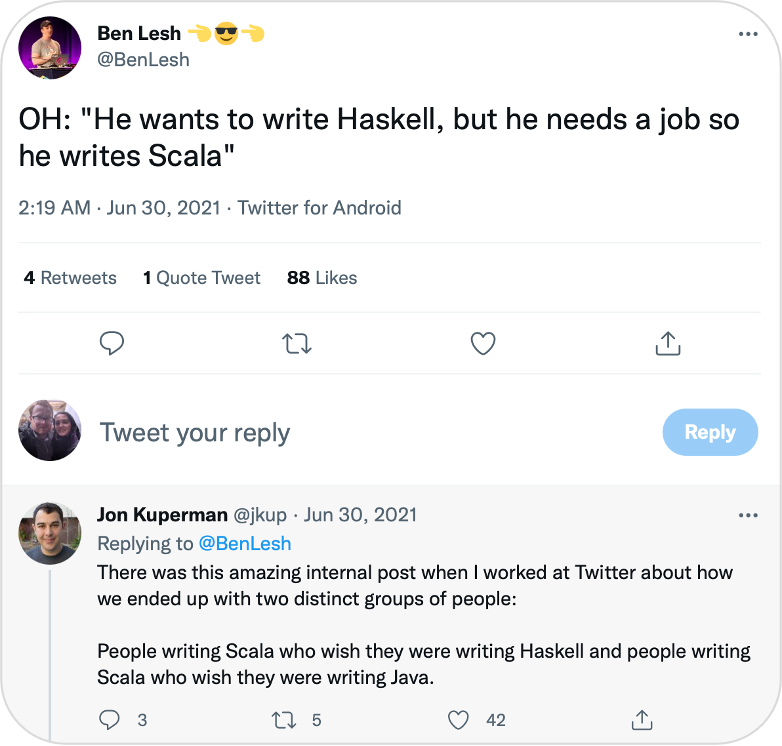

Ultimately, my biggest criticism of Monads in Python is simple: Monads aren’t Pythonic. The idea of code being Pythonic might seem a bit ideological or cultish to you, after all does it matter if our code is Pythonic if it works? I think it does. The danger we get into when we start introducing concepts like Monads into our Python code is that it very quickly stops looking and, more importantly, behaving the way someone could reasonably expect Python code to look and behave. Especially in a professional setting, that’s a problem. Imagine you’re working on a project, and you’ve made your entire codebase ultra-functional; exceptions don’t get thrown, everything is wrapped in Either and IO, you’ve written your own custom Monad transformers, all your functions are curried and so on and so forth. What happens when you roll off the project and another Python developer takes over? Well, in theory it should be fine - they write Python and you’ve written Python, except not if the Python you’ve written looks like Haskell or Scala. The point is perfectly summed up by this Tweet:

My strong feeling is that if you’re going to write your code in a way that means it ostensibly looks like Haskell (or Scala or Clojure or OCaml or F# or any other functional language you can think of), then you should just write your code in that language rather than trying to warp another language to the point of it looking alien to anyone else who develops in it. It’s precisely for this reason that the title of the blog is Pragmatic Functional Programming in Python, not Learn You a Python for Great Good. When it comes to FP, we should be pragmatic, taking the parts of the paradigm that work for us and make our code better and not worrying ourselves too much about the parts that don’t.

If you’ve gotten this far in the blog, it might feel like I’ve just told you that you should throw away everything you’ve read so far because none of it is Pythonic and you should never do it. Is that case? No. Firstly, regardless of whether you decide to use Monads, I think an understanding of them is vital when learning about FP because you’ll see them referred to everywhere, even if you don’t utilise them in your own code (plus, it’s not as if a language like Scala is alien in the data engineering space – there’s a good chance you’ll end up using it and come across Monads). Secondly, your decision to use or not use Monads should be one made based on an understanding of their pros and cons, not because you read a blog where someone told you that using Monads in Python is bad.

If I’m saying that I don’t like the Monadic approach to function composition and side-effecting in Python, what’s my alternative (and how does this all relate to testing, my second criterion)? Well, that’s exactly what I want to talk about in Part 2 of the blog, specifically, I want to talk about in future posts, specifically:

- Abstracting behaviour with decorators

- Function composition with pipes

- Type hints and static type checking

- Writing declarative code more broadly, and

- Unit testing